Sales Mathematics

Have you ever noticed that the moment a company needs to sell you something, the fundamental laws of mathematics take a coffee break? I went to a regular business school, but there must be a secret school where marketing majors learn that numbers are merely suggestions, like a pirate code, but for selling toothpaste.

Let’s take a field trip to this bizarre numerical universe.

1. The “More Than” Multiplier: This is a classic. A shampoo bottle proudly declares it provides “Up to 100% less frizz!”

-

What they mean: In one specific laboratory test, under a blue moon, with a hair strand from a model, they observed a slight reduction in frizz.

-

What you get: Your hair is still a frizz-ball, but now it smells like a tropical fruit that doesn’t exist in nature. You also feel a vague sense of mathematical betrayal.

2. The Percentage Ploy: You see a banner ad screaming, “LOSE 500% MORE BELLY FAT WITH METABO-BLAST!”

-

The Reality: 500% more than what? More than sitting on your couch and doing nothing? More than eating a whole cheesecake? More than a garden slug? The baseline is mysteriously absent, because the second you define it, the magic vanishes. If you lose 1 ounce of fat by crying over your bills, then 500% more is… 5 ounces. Not quite as impressive.

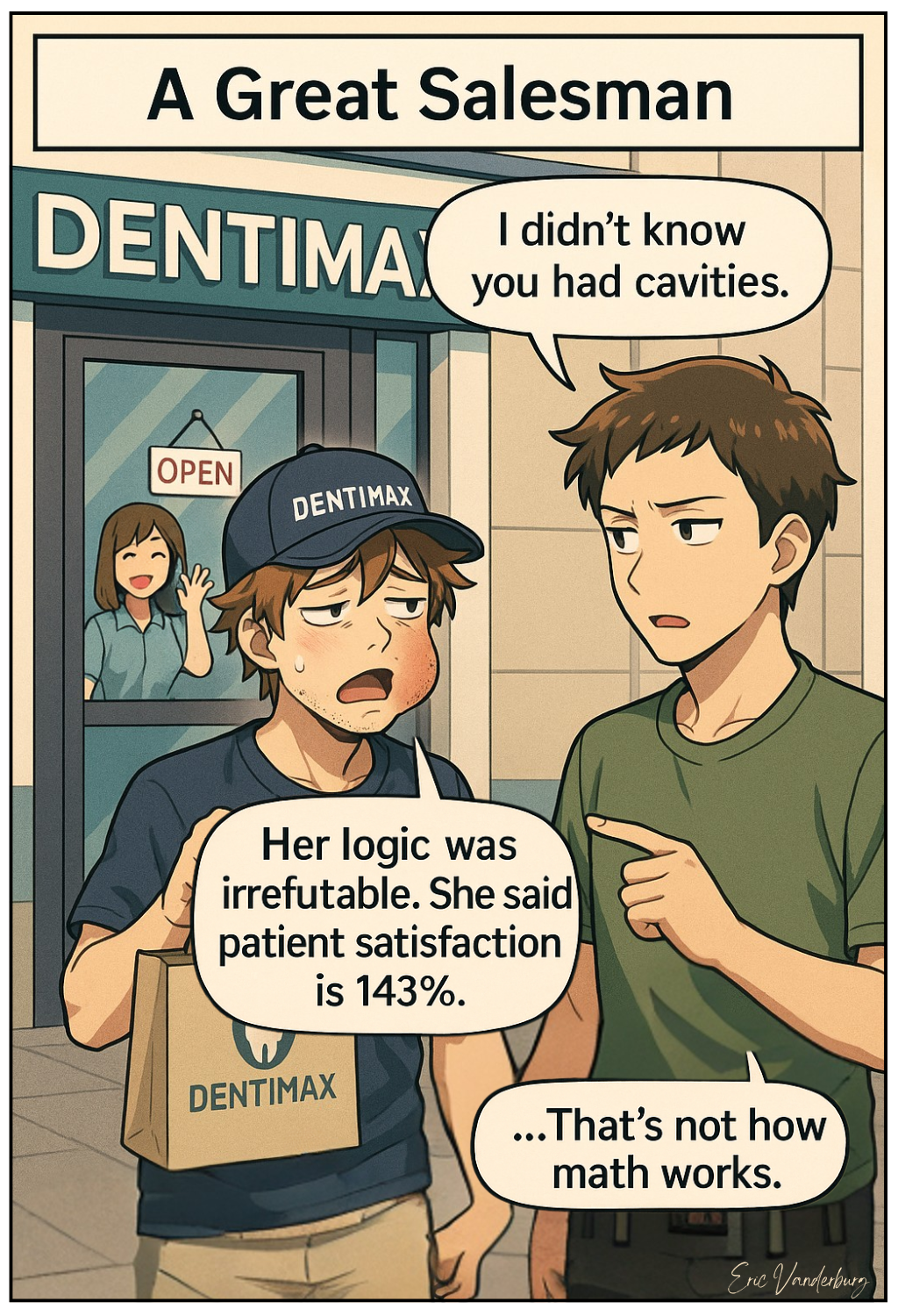

3. The “9 out of 10” Anomaly: The TV advert says, “20 out of 14 patients recommend DentiMax!”

-

Let that sink in. They didn’t just fudge the numbers; they broke the space-time continuum of statistics. They somehow surveyed 14 people, got 20 recommendations, and must have convinced six people so thoroughly that they voted twice. The salesman who came up with that doesn’t just get a bonus; he gets a Nobel Prize in Mathemagics.

4. The “Free” Equation: This is advanced calculus. “BUY ONE, GET ONE 50% OFF! (IT’S LIKE GETTING ONE FREE!)”

-

The Logic: No, it’s like getting one for 50% off. If I buy two $10 pizzas and get the second for $5, I spent $15. I did not get a free pizza. I got a discount on a second pizza. Calling it “like getting one free” is like saying getting a papercut is “like winning the lottery” because in both scenarios, you’re involuntarily bleeding.

Conclusion:

We navigate this world where numbers are elastic, percentages are pulled from thin air, and “savings” are a philosophical concept. The next time you see an ad, don’t ask, “Is this a good deal?” Ask the more important questions:

-

“What is the sample size of your survey? Were they all your cousins?”

-

“Can you show your work on that percentage?”

-

“If 20 out of 14 people love your product, are the extra 6 people from a parallel universe, and if so, do they offer interdimensional shipping?”

In the end, advertising math isn’t about truth. It’s about possibility. The possibility that somewhere, somehow, numbers are just happy little suggestions that can make you feel better about buying that third air fryer. And honestly, who are we to argue with 143% of that logic?

Discussion ¬