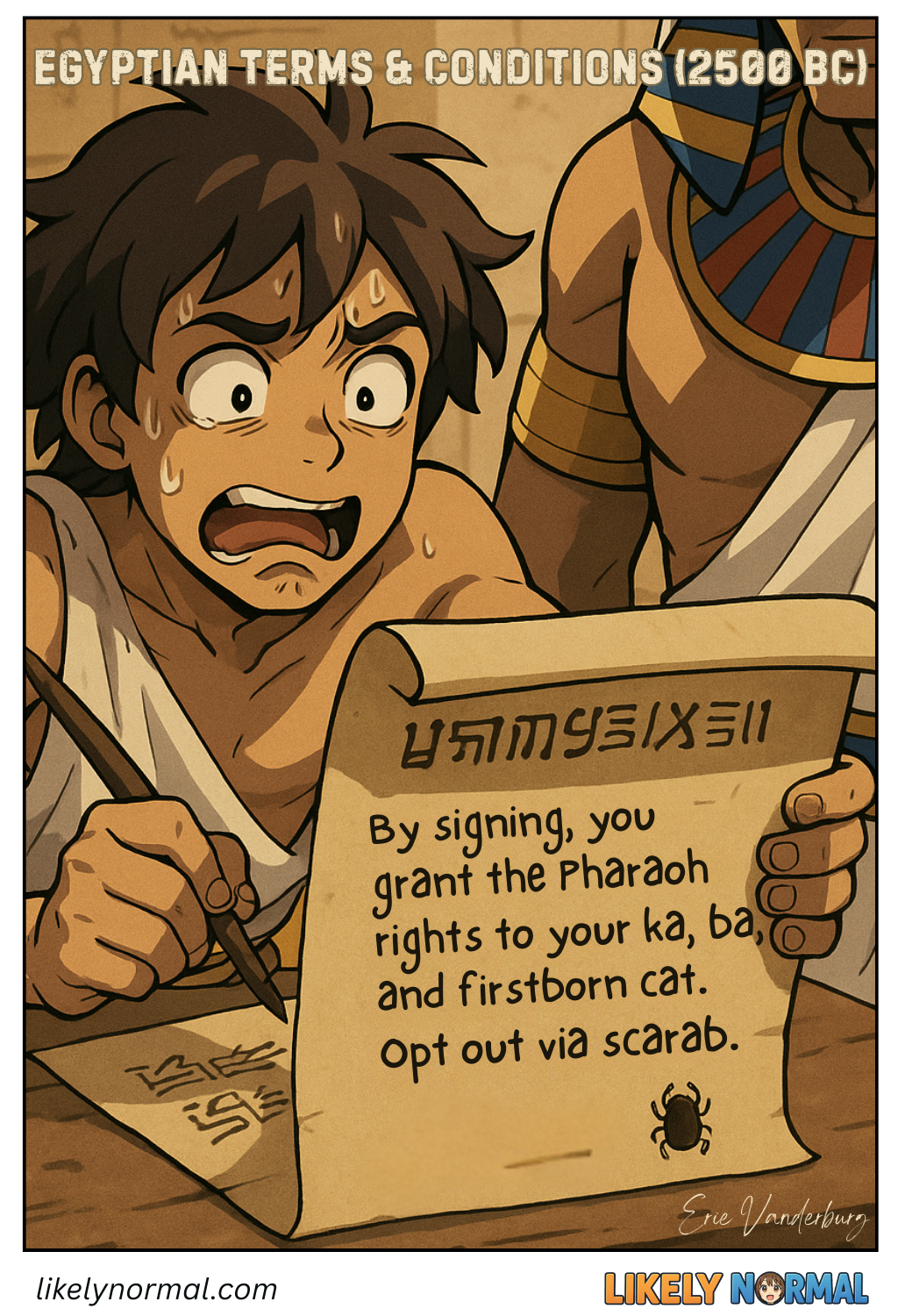

Egyptian Terms and Conditions

Every time you click “I Agree” on a software license, you’re participating in humanity’s greatest shared delusion—the collective pretense that anyone has ever read those 50 pages of legalese. These digital contracts are less like binding agreements and more like a hostage situation where a robot lawyer with a thesaurus addiction writes the ransom note. Remember Windows 95? Its End User License Agreement (EULA) was longer than the Gettysburg Address but with 100% more clauses about not reverse-engineering the software to, presumably, build a death ray. And let’s not forget iTunes’ legendary “no nuclear weapons” clause, which single-handedly prevented world chaos by ensuring dictators couldn’t sync their iPods before launching missiles.

Modern licenses have evolved into absurdist performance art. That “update” you just installed? It probably includes a provision requiring you to water the software company CEO’s houseplants twice a week. Buried somewhere in the terms is definitely a line about forfeiting your right to complain when the program crashes mid-document—because you clicked “Accept,” and in the eyes of the law, that means you totally knew the risks. The best part? These agreements are designed to be unreadable, full of phrases like “sub-licensable, royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable” that sound like they were generated by a legal jargon bot.

And yet, we all keep clicking. Why? Because the alternative is living like a hermit, writing letters by candlelight, and never again experiencing the joy of your printer driver demanding you agree to 17 pages of terms just to output a grocery list. So here we are—a society that skims 280-character tweets but blindly accepts 28,000-word licenses, all while quietly suspecting that somewhere, buried in Section 37, Subparagraph B, there’s a clause that technically makes us liable if the software accidentally orders 1,000 pounds of shrimp to our house. But hey, at least we didn’t have to read it. Terms and conditions may apply

Discussion ¬